The Hollywood Analogy

A scientific renaissance is arising amidst the ruins of a golden age.

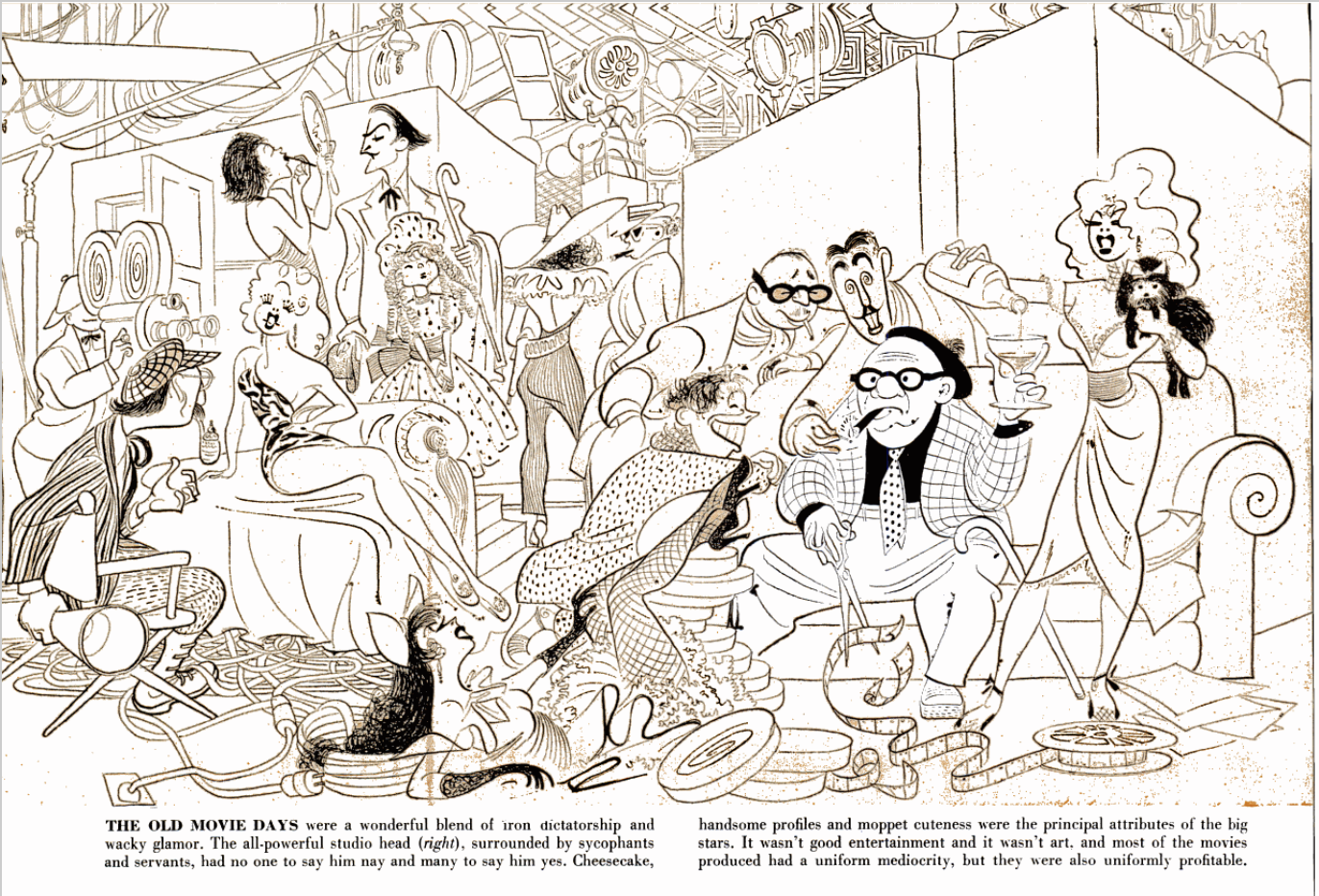

It took a decade for Hollywood's "Golden Age" to end, and almost no one mourned the loss.

Despite the moniker, the movies had stopped being good and were no longer making money. The 1950's became a transition period from old to New Hollywood, from studio-dominated monopolies to a network of talent-oriented projects managed by mostly independent producers. The demise is usually attributed to the antitrust case against the studios and the rise of television, but it was a host of compounding factors. No matter how tight a grip powerful institutions or companies hold, industries always evolve. And when the tides of change do breach the levy, transformation can happen quickly.

1950's Hollywood is fun history for film buffs, but it doubles as a useful analogy for understanding the current institutional changes underway in science, especially for trying to predict how the new scientific world order might look. The golden age of science may be drawing to a close, but something better is coming.

For the unfamiliar, a good source on the Hollywood transition is an article written by Eric Hodgins in a 1957 issue of LIFE magazine: "Amid Ruins of an Empire, A New Hollywood Arises" which documents the story in stark economic detail:

"A vast revolution has changed Hollywood from top to bottom in the course of a few explosive years. The revolution did not change merely a few externals; it changed an entire society. As always with a revolution, this one took place at the point of a gun. As always with a revolution, the times were ripe and the old order flabby. Two groups of people, in consequence, have found and used an opportunity. The first of those comprises what Hollywood calls Talent — meaning men and women who can actually direct, write or act in movies themselves. The second group is the Independent Producers — meaning producers independent of the major studios, or almost so. On those two groups hang all the law and the profits of the New Hollywood, the part of it that still makes movies for the theaters.

This New Hollywood is characterized not only by better movies but by a host of other radical innovations. The old time studio is undergoing an incredible face lifting, and the old time studio head has all but vanished. The financial structure of movie-making has changed so completely as to be unrecognizable... An Empire has fallen, but something better than an Empire is rising up."

Hodgins got the nuanced story right, and with financial precision. The heart of the issue was contractual—a grand renegotiation of power and profits that left most people better off and the end product much better. The slowest-moving and stubborn studio heads were the only real losers. They couldn't let go of a model that worked in a bygone era of influence and easy money. With the long view, we can see how the shift helped everyone win: the studios evolved, the talent reigned, and Hollywood continued to thrive.

Here and now with academic science, we can see echoes of something similar: a grand renegotiation driven by economic realities, new institutional players, and the need for a better product. The pendulum of power is swinging towards the scientists, and that bodes well for everyone.

TLDR for scientists: You have more power than you realize. You can and should renegotiate your relationship with academia.

TLDR for investors: There’s a new asset class emerging in commercializeable research. Early movers will reap the largest gains and potential network effects.

TLDR for universities: Fighting these changes will be costly. Embracing them will be uncomfortable and rewarding.

The End of the Endless Frontier

Science has long been showing signs of a tired golden age and imminent rearrangement. The current era of industrial-scale science is nearly 75 years old. It traces back to the post-WWII era in the United States and specifically to the ideas of Vannevar Bush. His perspective on how science should be organized and funded is clearly stated in his famous Science The Endless Frontier report to Franklin D. Roosevelt, which laid the foundation for the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institute of Health (NIH), and the basic research functions of the university system that we know today.

The system has held because the system has worked amazingly well, churning out research and ideas that have fueled much of the technology and progress our society has enjoyed. And it's been well funded, too. In the early 1950s, the U.S. government was spending less than $1B/year on research at universities and colleges. The launch of Sputnik set off a wave of federal research spending, increasing sixfold by the 1970s and well over $100B/year today.

But some people have started to wonder: maybe money isn't everything?

Patrick Collison and Michael Neilsen wrote in the Atlantic that the return on scientific investment is diminishing. They acknowledge the difficulty in measuring scientific returns, and instead tied numerous anecdotes and data sets together to show that science funding was “getting less bang for its buck.” The factors of the slowdown, they hypothesize, could be the rising costs of research—a function of the increasing numbers of people involved as well as the added training needed to make discoveries. Regardless of what’s causing it, they argued, improving the pace of discovery is paramount.

Many people have seemingly taken them up on this challenge. The growth of para-academic organizational experiments in science has been dizzying, with new efforts announced on a near-monthly basis. And the trend seems like it's just getting started.

In the past few years, we've seen numerous new organizations go from idea to reality. In November of 2020, Adam Marblestone and Sam Rodriques published a paper proposing new Focused Research Organizations (FROs) — time-bound, problem-oriented assemblages of scientific and technical talent to accomplish a specific goal that's holding back better science for everyone. A year later, several FROs are incorporated and building teams. There has been a rise in new, private operating institutions like the Arc Institute and Arcadia joining the club of new tech-funded operations like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) and Parker Institute for Cancer Immunology (PICI).

There's also a much stronger entrepreneurial ecosystem surrounding scientists than a decade ago, with groups like Y Combinator, Petri, and Flagship Pioneering serving as company-building factories. There are non-profits like New Science and Activate providing fellowships, mentorship, and community to scientists with bold ideas. There’s swelling enthusiasm from “DeSci” entrepreneurs who are using the new web3 tools to prototype every conceivable idea; new DAOs and science NFTs are announced every week. The momentum has also reinvigorated the decades-long work of open science pioneers and advocates, helping them find supportive new audiences for their messages and lessons. Each of these new players has a nuanced model and operating plan, but a common vision for the future: better science. Not just more papers, but genuine scientific freedom that leads to discoveries that translate into real-world outcomes and applications.

There's a term from evolutionary biology—adaptive radiation—that describes the rapid diversification from a single ancestral species into a variety of new forms and anatomic configurations, usually in response to a change in the environment or ecological opportunity. Darwin's finches are a classic example. The theory suggests that despite the common factors going into the creation of these science organizational experiments, each one of these projects might very well end up in a different place, with a different structure, and filling a different niche. And that’s probably a good thing. As Marblestone phrased it to me: "why do we only have a small number of structural tools for organizing research when there are so many different kinds of genuinely different research?"

With everyone moving quickly in new directions, it can be hard to predict the shape of what's to come. This is where the Hollywood analogy becomes useful. And the lesson for the old order is simple: adapt.

Hollywood’s grand renegotiation was an opportunistic moment for those who moved with the times, and difficult for those who fought against the change. The agents, like Lew Wasserman at MCA, and others who sided with the talent were obvious winners. But so were the old studios who adapted fastest to the changing environment.

“It’s hard to define an independent producer except to say that, by definition, he is not tied up in cement. With the one exception of Sam Goldwyn the independent does not own his own facilities. Either he contracts for them and arranges his own financing, or else he exists inside a major studio but has so much autonomy that he is mostly or wholly a law unto himself. The pragmatic test is this: if you can turn around fast, you are an independent. If you cannot, if you are all tied up in cement, you are not an independent.

Today the battle lines are more or less drawn between these two types of operation. The feline powers of speed, suppleness and balance possessed by the independents give them a certain great advantages over the majors. Some majors, like Paramount, are extremely well administered and have a head start because they very early made working deals with many independents. Some others, like 20th Century-Fox, are fast adapting themselves to the new ways."

The futures of the new science organizations are bright. They all appear to have attracted enough funding to do something interesting. Speed and flexibility come easy to them, and the shifting tides will only help their cause. The larger questions hang over the legacy institutions, like the universities and federal research labs. My prediction: the ones that take advantage of these emerging trends will thrive by bringing in new resources, retaining top talent, and remaining at the cutting-edge of research. Others will cling to outmoded processes and procedures while slowly bleeding talent.

Like the Hollywood story, this is a contractual revolution. This isn’t a dramatic end of universities or the complete privatization of research; it’s mainly the outsourcing of the technology transfer function—the process of bringing discoveries out of the lab and into the world—from the universities to the new players. And this new arrangement has important follow-on effects for the entire research ecosystem.

Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) at universities are a relatively new idea in scientific timescales, having come about as a consequence of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980. The law allowed federal grant-receiving entities to keep ownership of any intellectual property they create instead of leaving it with the funders (the federal government). Universities, the largest recipients of federal grant funding, suddenly became the owners of vast intellectual property portfolios. But they haven't proven to be terribly efficient managers. Most TTOs are unprofitable. The incentive structure and the messaging from their leadership suggest they aren't even trying, using language that implies their work shouldn't be about profitability, instead of saying it "advances universities' overarching missions of research, education, and service."

This is all changing in the grand renegotiation. The new organizations are giving TTOs a newfound purpose by offering a contractual olive branch: funding and infrastructure in exchange for first rights on commercializing the work. The Parker Institute (PICI), for example, has relationships with a number of academic institutions. The individual scientists who receive funding from PICI are able to access the resources without having to leave their university. PICI, in turn, manages any intellectual property in a way that leverages their Silicon Valley connections and streamlines the path from discovery to market application. From this new, unique niche in the scientific ecosystem, PICI has found a way to bring new collaborations, datasets, and companies into the world.

The concept is creating an entirely new investment class in the form of commercializable research and could bring billions of dollars into the research ecosystem. This is already happening. Northpond Ventures has a deal with the Wyss Institute of Harvard to fund “solutions-oriented research and development” in return for a right of first refusal on commercial efforts. Deerfield Management has a similar arrangement with the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. My prediction is that we’ll see dozens of VC announcements along these lines in the coming year, as well as new scientific grant programs for early-career scientists from those same VCs. [1]

Instead of TTOs serving as gatekeepers to researchers and ideas, this updated arrangement is turning them into fundraisers and dealmakers. This is a fault line I'm watching closely: which university administrators will ride the new wave and which will fight it?

The other side of this coin is, of course, what it means for scientists.

Founder-Led Science

"Only a little oversimplified, this is what happened. Talent today demands every last dime it thinks the traffic will bear. The studios, not without shuddering, are forced to give down.

In New Hollywood, with the old monopolies gone and the czardoms toppled, the law of supply and demand is working just as Adam Smith always would. Talent — meaning stars, directors, producers, and writers — is reaping rich rewards because Talent is scarce."

In Hollywood's grand renegotiation, talent was the biggest winner. The stars emerged from their decades-long serfdom under the control of the studios to a time of radical freedom and prosperity. In New Hollywood, stars were the differentiating factor to profitability, and they finally negotiated a paycheck to reflect it. It wasn't just cash, either. They wanted equity and upside, and they got it. Hodgins goes into the details on the deals of Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, and others, as well as how they legally structured themselves into person-oriented production companies.

We’re already seeing this in science. The reports of million-dollar salaries from Altos Labs, the headline-grabbing longevity company, are causing eyebrows to raise in scientific circles. With the boom in new organizations, it almost doesn't matter which model is "right" at all. The important thing is that there are increasing options for the most talented scientists. The optionality is giving rise to competition, and many scientists are becoming starkly aware of just how much they're worth. This has a monetary component, but it has more to do with scientific freedom and the ownership of new ideas, especially in terms of the commercialization of research.

Scientists have always been wooed to industry with big paychecks and consulting gigs. This is different, especially in the life sciences. Over the past year, biotech scientists across Twitter erupted with a new slogan: "founder-led biotech." The term was helped to popularity by Tony Kulesa, a scientist and venture capitalist, to describe the changing leadership demographics of the breakout biotech companies like Ginkgo Bioworks and AbCellera. The leaders were all scientists.

Kulesa's rallying cry struck a nerve. The essay led to a conference and, more importantly, an identity shift for many young scientists who started making active plans to control their own destiny. On campuses across the country, a new student-led initiative called Nucleate (which Kulesa advises, but doesn’t lead) has become a membership club for these folks, with swelling numbers and dozens of spinout companies already. To hear Kulesa describe it, the trend is two-fold — the rising ambition of the scientist is being matched by an emerging ecosystem of supporters who are eager to receive them on this new path. From Kulesa’s essay:

The success of this bow wave of companies is catalyzing more investor interest in the founder-led model. Investors in these early successes are doubling down on their support for founders, and others that sat on the sidelines are now getting in the game. They are drawing on the models in tech for supporting founders with a platform for critical business needs like recruiting and business development, and creating platforms specialized to biotech. The rest of the service ecosystem is responding as well. For example, lab space that is rentable month-to-month is becoming available in most research hub cities.

It's hard to put that enthusiasm back in the bottle. It's a self-reinforcing loop of empowerment and infrastructure, similar to the shift that happened in Hollywood. Hodgins again:

"Today a star is less a star than a comet, speeding through the skies with a stream of luminescent gas behind him in which it takes no telescope to discover his agent, his tax attorney, his investment adviser, his business manager, his public relations counsel and other functionaries essential to the tax and deductability age."

This doesn't mean that every scientist will become a CEO. That's beside the point. Agency is the main event. Judging from an interview with the Parker Institute (PICI) researchers who founded Arsenal Bio, the role of Sean Parker and PICI has been one of early and enduring support, coupled with heavy scientist involvement and upside in the companies that are formed as a result. If not explicitly founder-led, certainly scientist-driven. That bodes well for the prospect of more good science finding its way into the world.[2]

Critics will say that "science isn't about the money" or that the "value of research can't be measured" but they're missing an important point. Sometimes science is done for its own sake—true curiosity-driven research—but it’s often done for a purpose. The basis for our modern science infrastructure is steeped in intended outcomes. In Science The Endless Frontier, Bush repeatedly lists the goals: curing disease, national security, creating full employment. Where and when science is being done with a goal in mind, the system should be improved to achieve it. The new scientists are rejecting the simple story about the purity of research, and building a better bridge from the lab into the world.

This story goes far beyond company-building and economic output, too. The newly empowered scientists, with the freedom to achieve outcomes on their own terms, are already rewriting the rulebook for how they do science. The founders of Arcadia have decided to operate as a journal-independent outfit, meaning they will not be publishing their results in peer-reviewed journals. They're going to publish quickly and openly in new ways, but they're not going to spend time or money with journals. It's a stunning announcement. With one blog post, they're leapfrogging towards the open science future that advocates have been articulating for the past few decades. New ideas and progress towards preregistration or micropublications could be next. With more bold leadership, open science could see more progress in the next two years than it has in the past twenty.

"The new turn of the wheel has brought about what no number of exhorting councils for better films could ever have done: it has made Hollywood really avid for unique, specialized, distinctive, hand-monogrammed, individual successes. With the assembly line broken down and the mass production methods of the past made obsolete, no other key to profits, or even to continued solvency, was left. And then that truth burst at last upon the boulevards, the new race for Talent began."

With the benefit of time, we know what came of the Golden Age demise: a Hollywood Renaissance. A new generation of filmmakers burst onto the scene and transformed the medium. The films evolved stylistically, bringing realism and narrative complexity: The Graduate, Bonny and Clyde, Easy Rider. Technical advancements were commonplace as the movies moved off of the studio lots and incorporated more on-location shooting. Innovation and risk-taking were the new norms.

If the trends continue, we can expect a similar transformation in science: a new generation at the helm, steering and showing where science can take us in the 21st century.

Notes

[1] The most enlightened VCs play a longer game and focus more deeply on relationships. They understand that companies and entrepreneurial careers begin as projects with uncertain futures. Trying to securitize intellectual property before experiments and studies have even been run can be overkill in many situations. Meanwhile, the opportunity for a small grant to establish a trusting relationship is easier and, with the right person, more effective. Creating these types of relationships at scale takes a little more intent and investment, but can pay off. The market cap of all the Thiel Fellowship fundees’ projects is now hundreds of billions of dollars. We’re running these on Experiment now with groups like the FootPrint Coalition. I expect many new VC grant programs in addition to the new scientific investment funds.

[2] There's a compelling study from Norway that analyzed the economic output of their scientists after the government changed their system from that of “professor privilege”—a system where inventors and scientists maintained ownership over the ideas they generated—to one modeled after the United States’ system of University-managed technology transfer. They found that entrepreneurship, measured by both the quantity and the quality of companies started, dropped precipitously after the removal of professor privilege. If that research holds, we should expect these new science organizations to yield a bumper crop of valuable new companies.

Thanks to Sam Rodriques and Tony Kulesa for inspiration and feedback on this essay.